After 4A and 4B, in the late seventies the Italian physicist Giuseppe Di Giugno realizes at Ircam the 4C digital signal processor.

Brief History – The 4B machine was finished in 1977, and already in January, 1978 Di Giugno started working to the 4C, the third processor among those commonly called 4N and developed by the Italian physicist. Even the 4C was designed to be implemented on a single printed circuit board and interfaced with a PDP-11/55 computer. The work started with Alain Chauveau as collaborator, since with Di Giugno formed the staff of the Department of Electroacoustics, directed by Luciano Berio. The 4C DSP, with all the new features, was finished in the month of May.[1]

SYN4B – The most important problem with the 4B was the difference between the sampling rate of the processor and that adopted to generate envelopes; a problem that caused an unexpected and annoying noise.[2]

The First Year – The 4C project was the most important for all the 1978, furthermore this is the first full year of the institute direct by Pierre Boulez (open in 1977) and so all researchers participated to this project with a lot of stress. In addition to Di Giugno e Chauveau, even Didier Roncin take part to the research (as responsible for the different versions of the 4C), then Curtis Abbott, Jim Lawson and Jean Kott, engaged to design control software for the 4C.[2]

Technical Features – The 4C processor was optimized for digital synthesis, and structured essentially with micromodules interconnected. User could use up to 16 waveform. Lightly software was developed for managing functionality and interconnectivity of the micromodules, they could be saved in a read-only memory, so the 4C could operate at a higher speed. Because there were link through modules used more than others, Di Giugno and Jean Kott realized some subroutines to recall saved configurations, many of which considered standard.[1] Finally, we must not forget that the 4C could be used as external peripheral, in conjunction with traditional programming languages such as Music V and Music 10, in those years available at Ircam.[1]

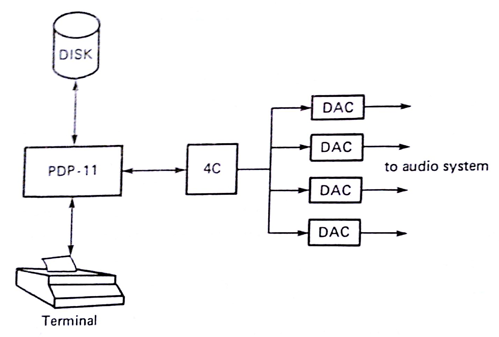

The 4C system – Beyond his specific technical features, we don’t forget that the 4C processor was an element in a more large and sophisticated and system for computer music. in particular there were two typical configurations for this system: first, one that we could define light; with a bidirectional link towards the PDP-11 computer (in turn linked to a memory and controlled with a teletypewriter) and four DAC, as show in the picture:

Una configurazione light del sistema 4C.

This light version allowing users to synthesize sounds in real time, taking advantage the potentiality of 64 oscillators, 32 amplitude envelopes and 16 KHz of sampling rate for a better performance (higher sampling rate = higher instability).[2]

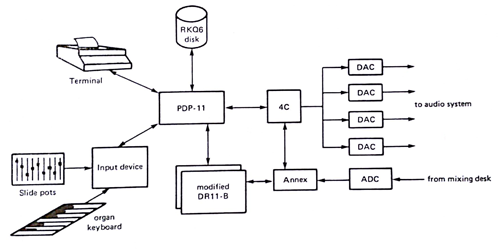

Standard Configuration – A second configuration, named standard by composers who worked at Ircam, had a much more complex configuration but also higher performance.

From the previous picture we can notice the availability of controllers (already implemented with the 4B) and, most important, a switch Annex, designed by Peter Eastty, useful to connect an ADC of high quality (realized by Tim Orr) to a memory with direct access that gave the possibility of digital recording or processing external sounds in real time. Loading external sounds was the most important new feature of the 4C processor.[2]

External Controllers – The availability of controllers for the 4C, contributed to make this device very powerful, if compared with similar devices of those years, and, more important, to make the 4C a real musical instrument. From this viewpoint, very interesting was the realization of a new external controller designed by Max Mathews and dedicated to the processor of Di Giugno: the Sequential Drum, that could be hit like a drum to send data to the 4C.

4Ced – Even for designing the Sequential Drum was very important another software project, called 4Ced. This is a software for managing the 4C processor, and it was developed by Curtis Abbott. It seems that even Pierre Boulez wanted to use this device, perhaps for a new version of Explosante-five.[1]

First Performance – On that occasion, the 4C was interfaced with a PDP-11 computer of the Electroacoustic Department, while controllers placed in the acoustic room. After a week, the 4C was used for the work Wellespiele by Swiss composer Balz Truempy at Donaueschingen Festival, Germany. Here, the 4C was interfaced with a PDP-11/40 by Digital Equipment Corporation (Germany), and the digital instrument was designed by Neil Rolnick (even performer) with the author, and programmed by Giuseppe Di Giugno and Jean Kott.

Next advancements – Though the 4C system had some success, Di Giugno began to work on a new digital processor named 4X, far more sophisticated and even more famous.

References:

[1] Gerald Bennett, Research at Ircam in 1977, Rapports IRCAM, Centre Georges Pompidou, Parigi, 1978.

[2] James Moorer, Alain Chauveau, Curtis Abbott, Peter Eastty, James Lawson, The 4C Machine, in Foundations of Computer Music, edited by Curtis Roads e John Strawn, The MIT Press, 1988.

[3] Curtis Roads, Interview with Max Mathews, Computer Music Journal, Vol. 4 [4], 1980.